Abstract

Purpose

Substantial evidence supports the benefits of an intensivist model of critical care delivery. However, currently, this mode of critical care delivery has not been widely adopted in Korea. We hypothesized that intensivist-led critical care is feasible and would improve ICU mortality after major trauma.

Materials and Methods

A trauma registry from May 2009 to April 2011 was reviewed retrospectively. We evaluated the relationship between modes of ICU care (open vs. intensivist) and in-hospital mortality following severe injury [Injury Severity Score (ISS) >15]. An intensivist-model was defined as ICU care delivered by a board-certified physician who had no other clinical responsibilities outside the ICU and who is primarily available to the critically ill or injured patients. ISS and Revised Trauma Score were used as measure of injury severity. The Trauma and Injury Severity Score methodology was used to calculate each individual patient's probability of survival.

Results

Of the 251 patients, 57 patients were treated by an intensivist [intensivist group (IG)] while 194 patients were not [non-intensivist group (NIG)]. The ISS of IG was significantly higher than that for NIG (26.5 vs. 22.3, p=0.023). The hospital mortality rate for IG was significantly lower than that for NIG (15.8% and 27.8%, p<0.001).

More than one quarter of trauma patients are admitted to ICU for optimized critical care and it plays a major role in not only survival but also improving prognosis of functional outcome following injury.1

There are two broadly used models of critical care delivery in managing the major trauma patients. "Open" intensive care unit is one model in which the surgeon is primary supervisor for postoperative care including the provision of critical care service and ICU can provide an advanced monitoring and organ support for such patients.2,3 "Closed" intensive care unit or intensivist-model ICU is the alternative model in which certified physician known as intensivists are primarily available and responsible for managing the critically ill patients in ICU to provide critical care.3

Evidence supporting dedicated intensivist staffed ICUs is growing, and have shown intensivist-model ICUs to be associated with reduced mortality and length of stay in the hospital and the ICU.4,5 However, this model of critical care has not been widely adopted in Korea, and studies demonstrating the benefits of such a model are limited.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and potential benefits of an intensivist-model ICU after major trauma in terms of hospital mortality in a single tertiary teaching hospital.

This study was carried out in an 895-bed tertiary teaching hospital. The Surgical Intensive Care Unit comprised a 27-bed unit where care was offered to surgical patients from varying specialties (general surgery, neurosurgery, cardiothoracic surgery and orthopedic surgery) including trauma.

During the two-year study period, a total of 363 patients [Injury Severity Score (ISS)>15] were registered with our trauma registry. Patients who presented with no vital signs and were pronounced dead before admission to the ICU were excluded, as were patients who were admitted to the general ward, patients who transferred after their acute care and patients whose Glasgow Outcome Scale was missing. One hundred twelve patients were excluded, yielding 251 possible patients eligible for review.

Pre-hospital services were provided by emergency medical technicians. Although Korean paramedic training requires Advanced Cardiac Life Support training such as electrocardiogram interpretation and advanced airway techniques, Korean paramedics operate as Basic Life Support crews with limited physician support. Although, recently, ongoing efforts have been made to improve pre-hospital care, the level of care was essentially same for our patient population.6

Our hospital provides 24-hour emergency services and receives both direct admissions and transfers from other hospitals. The trauma team consists of emergency physicians and members from all surgical specialties. Clinical management follows the Advanced Trauma Life Support principles. After initial stabilization or even during active resuscitation period, attending emergency medicine physicians judge the need for an intensivist to participate in the care of trauma victims.

In the intensivist care model [intensivist group (IG)], a physician board certified in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery as well as critical care assumed primary responsibility for trauma patients. The intensivist was present during daytime hours and provided clinical care exclusively in the ICU, and returned pages within 5 min 95% of the time during off-hours, as suggested by the Leapfrog group.7 Care was coordinated by five clinical nurse specialists in our hospital. If a staged operation was deemed necessary, surgical consultation was obtained and performed, and the intensivist assumed primary responsibility until the patient was discharged from ICU.

In the conventional open care model [non-intensivist group (NIG)], the operating surgeon assumed primary responsibility for the patient. In-house residents were typically involved in primary surgical decision making and writing orders. A liberal consultative policy was the norm with regard to the subsequent ICU care of trauma patients.

This was a retrospective study of prospectively collected data obtained from trauma registry of a single university hospital from May 2009 to April 2011. In addition to patient demographics, anatomic and physiologic measures of injury severity were evaluated based on ISS and Revised Trauma Score (RTS), respectively. Furthermore, probability of survival (Ps) for each individual patients were calculated based on Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) and using appropriate coefficient, the score for penetrating and blunt injuries were calculated separately.8 Given the exceedingly high preventable death rate in Korea and being a younger trauma care system, we used relatively old coefficients reported in the literature. All the variables were collected by a designated trauma coordinator and reviewed for their completeness and accuracy by emergency medicine physicians and surgeons.

Data were assessed for normality of distribution using Kolmogoroff-Smirnov's test with Lilliefors correction. Significant differences between the cohorts were determined using Student's t-test (parametric data), and Fisher's exact analysis. All t-tests were two-tailed and a significant difference was defined as p<0.05. All statistics were performed using SPSS software, version 12.0, for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

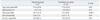

Of the 251 patients, 57 patients were treated by an intensivist (IG), while 194 patients were not (NIG). Table 1 lists the patients' characteristics including age, ISS, RTS, and Ps. Although the mean age, male gender (%), RTS, Ps (%) of IG and NIG were not statistically significantly different [47.6 years vs. 47 years (p=0.84), 71.9 vs. 68.6 (p=0.27), 6.45 vs. 6.27 (p=0.49) and 78.9 vs. 78.5 (p=0.91), respectively], we noted a statistically significant difference in mean ISS between the two groups (26.5 vs. 22.3; p=0.023).

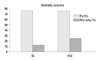

Fig. 1 shows a significantly lower crude mortality rate for IG (9/57) compared with that for NIG (54/194) (15.8% and 27.8%, respectively, p<0.001), yielding a crude relative risk reduction (RRR) of death (%) of 43% (4-67%, 95% CI).

This study compared two approaches for the management of patients with severe injuries in a surgical ICU. The nonintensivist model (NIG), where patients are managed primarily by nonintensivists aided by consultants, is more characteristic of the way in which critical care medicine is practiced in Korea. In contrast to the NIG, the intensivist model (IG) is an alternative, where an ICU service comprehensively managed by intensivist during the patient's stay.

Modern inclusive trauma systems are concerned with injury prevention, prompt pre-hospital care, effective resuscitation, early hemorrhage control, high quality critical care and early rehabilitation. In the United States, a process of trauma center verification and designation ensures the availability of standard trauma care and quality assurance. According to a resource document published by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, Level I trauma centers are required to staff a surgically directed ICU physician team.9 Also, as described earlier, the Leapfrog group recommends following hospital safety standards supported by evidence-based research, including those for ICU care and ICU physician staffing (IPS). Satisfying the IPS standard required staffing with intensivists, who manage or co-manage ICU patients to provide exclusive critical care including off-hour manages such as 95% of response to pages within 5 min.

In contrast to Western or European counterparts, no formal certification system for intensivists existed in Korea until 2009. Being a relatively young dedicated intensivist system, this study attempted to demonstrate the feasibility and benefits of intensivist-led critical care, especially in patients with major trauma, in Korea.

In this study, we observed better outcomes despite an increase in injury severity for our cohort. One possible explanation for our findings lies with the unpredictable nature of critical illnesses. In this regard, intensivists, by virtue of being present in the ICU and, therefore, immediately available, could be more interactive or proactive in the management of emerging patient care issues. In contrast, in nonintensivist-delivered care, daily patient rounds were typically made once per day early in the morning, at which time, strategic medical decisions were made for the day. Patient data was reviewed later in the day, but not bedside. Additionally, unanticipated problems were brought to the attention of the primary care team via an ICU nurse, leading to an inherent delay in their response.

Alternatively, outcome differences might have resulted from greater team leadership by an intensivist, rather than a less experienced resident or nonintensivist surgeon.10 Growing evidence suggests that organized critical care can influence outcomes. Hanson, et al.10 compared two different care models for surgical ICU patients. One group was managed exclusively by a critical care attending service team and the other by general surgery faculty and house staff. The critical care cohort involved a shorter ICU stay, fewer days of mechanical ventilation, and fewer complications, despite of increased severity of illness. In another report by Nathens, et al.,5 the authors demonstrated a 36% reduction in the risk of death compared with open units. We also observed similar benefits [RRR; (43%, 4-67%), 95% CI] for intensivist-led critical care in our cohort.

The potential advantages of intensivist-led care can be summarized as follows: 1) timely and frequent titration of therapy by being physically present, 2) easier implementation of evidence based protocols likely to benefit patients; 3) enhanced communication and collaboration with other clinicians and medical specialists to provide optimum care, and 4) greater feasibility for the ICU manager to standardize care, discharge patients in a timely manner, and evaluate performance.11

In the intensivist model, active pursuit of suggested best practices (early goal directed therapy, protective lung ventilation, early appropriate antibiotic therapy, early enteral nutrition, sedation protocol, etc.) was made to improve outcomes after major trauma, which could be a potential explanation of our better results.12 Numerous studies support the use of best practice check lists, and use of therapeutic bundles has been shown to be associated with improved outcomes.12-14

In addition to above mentioned advantages, if an intensivist is a surgeon, he/she can be actively involved in the initial resuscitation phase or operative phase in a emergency department when intervention is critically important or needed emergently, as we described previosly.15 Furthermore, Tinti, et al.16 demonstrated that transition to an intensivist model led to improved resident job satisfaction. Non-operative management of solid organ injuries has become common during the last four decades.17 Exposure to integrated critical care supervised by an experienced trauma surgeon-intensivist may not only improve resident job satisfaction and make our specialty more attractive, but may also improve patient outcomes.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to describe that an intensivist model of critical care is feasible after major trauma in Korea. However, our study did not compare complication rates or conduct a financial analysis of the cost implications inherent in caring for a patient with an intensive care service, which are warranted for further investigation. As there is an ongoing administrative effort to reinforce improved safety in the ICU at the government and society level, a more sophisticated study revealing the cost effectiveness of implementing this potentially life-saving approach is clearly necessary.

This study has three major limitations that might impact interpretation of the data. First, although the data was collected prospectively, the patients were not admitted to the ICU randomly, which might contribute to a selection bias. Furthermore, the study could be criticized in terms of its design, as this was neither a prospective study nor a case control study, and patient sampling was not performed because of the limited sample size. Furthermore, one could expect differences in the quality of critical care administered by a board-certified physician compared to a less experienced trainee. Although a randomized trial of critically injured patients might be a challenging ethical issue, further studies are needed for more solid evidence. Second, the mortality benefit of IG was largely based on improved mortality rate rather than expected survival by TRISS methodology. Validity of such classic parameters comparing other established predictors (e.g., Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation: APACHE score), however, has been a matter of intense debate.18 Although we acknowledge the inherent limitations of such indices in representing one's severity of injury and the potential gap between actual and expected risk of death, trauma mortality is a multifactorial process. Our cohort was characterized by similar clinical circumstances, such as ICU resource utilization, and only substantially differed in whether an intensivist was present or not, which might have minimized potential bias. However, this study was only able to provide descriptive information for a small number of observations, excluding details on the processes of critical care, including pre-hospital care, surgical intervention and preventive measures, that may have impacted clinical outcomes were not available for analysis, rendering it difficult to draw concrete conclusions. Third, several patients were transferred under the care of an intensivist for more advanced hemodynamic support, mechanical ventilation therapy and sepsis management during their ICU stay. Such patient crossover could have had some influence on the resultant hospital mortality rate. However, the number of these patients was relatively small, and we included these patients in the NIG, because the impact of the initial mode of critical care on mortality was the primary aim of the study.

In conclusion, intensivist-led critical care is feasible and might contribute to better outcomes after major trauma in comparison to current Korean clinical circumstances. The presence of a dedicated intensivist in the ICU is invaluable to the development of policies and protocols, and is thought to be important to assuring the immediate needs of trauma patients are addressed. This study may hopefully serve as a useful reference for challenging the ingrained concepts of ICU service in Korea.

Figures and Tables

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thanks to Dr. Hyeun Joo Baek and Mr. Jung Woo Lee for their assistance in manuscript preparation.

Notes

References

1. American College of Surgeons. National Trauma Databank. 2004.

2. Haupt MT, Bekes CE, Brilli RJ, Carl LC, Gray AW, Jastremski MS, et al. Guidelines on critical care services and personnel: recommendations based on a system of categorization of three levels of care. Crit Care Med. 2003. 31:2677–2683.

3. Brilli RJ, Spevetz A, Branson RD, Campbell GM, Cohen H, Dasta JF, et al. Critical care delivery in the intensive care unit: defining clinical roles and the best practice model. Crit Care Med. 2001. 29:2007–2019.

4. Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002. 288:2151–2162.

5. Nathens AB, Rivara FP, MacKenzie EJ, Maier RV, Wang J, Egleston B, et al. The impact of an intensivist-model ICU on trauma-related mortality. Ann Surg. 2006. 244:545–554.

6. Lee CC, Im M, Suh GJ. Time for change: the state of emergency medical services in South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2006. 47:587–588.

7. The Leapfrog group. ICU physician staffing fact sheet. Accessed on 2012 Feb 28. Available at: http://leapfroggroup.org/media/file/LeapfrogICU_Physician_Staffing_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

8. Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Copes WS, Gann DS, Gennarelli TA, Flanagan ME. A revision of the Trauma Score. J Trauma. 1989. 29:623–629.

9. American College of Surgeons. Reference Guide of Suggested Classification. Accessed on 2011 June 21. Available at: http://www.facts.org/trauma/vrc1.pdf.

10. Hanson CW 3rd, Deutschman CS, Anderson HL 3rd, Reilly PM, Behringer EC, Schwab CW, et al. Effects of an organized critical care service on outcomes and resource utilization: a cohort study. Crit Care Med. 1999. 27:270–274.

11. Pronovost PJ, Holzmueller CG, Clattenburg L, Berenholtz S, Martinez EA, Paz JR, et al. Team care: beyond open and closed intensive care units. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006. 12:604–608.

12. Stelfox HT, Straus SE, Nathens A, Bobranska-Artiuch B. Evidence for quality indicators to evaluate adult trauma care: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2011. 39:846–859.

13. DuBose JJ, Inaba K, Shiflett A, Trankiem C, Teixeira PG, Salim A, et al. Measurable outcomes of quality improvement in the trauma intensive care unit: the impact of a daily quality rounding checklist. J Trauma. 2008. 64:22–27.

14. Pestaña D, Espinosa E, Sangüesa-Molina JR, Ramos R, Pérez-Fernández E, Duque M, et al. Compliance with a sepsis bundle and its effect on intensive care unit mortality in surgical septic shock patients. J Trauma. 2010. 69:1282–1287.

15. Lee JW, Hwang JJ, Kim KD, Choi JH. Blunt cardiac and pericardial rupture without cardiac herniation: a diagnostic challenge. ANZ J Surg. 2011. 81:489–490.

16. Tinti MS, Haut ER, Horan AD, Sonnad S, Reilly PM, Schwab CW, et al. Transition to a semiclosed surgical intensive care unit (SICU) leads to improved resident job satisfaction: a prospective, longitudinal analysis. J Surg Educ. 2009. 66:25–30.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download