Abstract

Primary frontal sinus lymphoma is a very uncommon disease. In all the previously reported cases, the presenting symptoms have been due to the tumor mass effect. We present an unusual case report of an immunocompetent patient who presented with facial palsy, and then progressively developed other cranial nerve palsies over several months. He was later diagnosed with diffuse large B cell lymphoma originating from the frontal sinus. The patient underwent chemotherapy, but eventually had to receive autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. He is currently disease-free. The clinical course, diagnostic workup, and therapeutic outcome are described.

Lymphoma originating from the paranasal sinuses (PNS) is a rare entity, accounting for less than 0.17% of all lymphomas.1 Of the PNS lymphomas, most are from the maxillary or ethmoid sinus, while primary frontal sinus lymphomas are extremely uncommon. PNS lymphoma patients usually present with symptoms resulting directly from the presence of the tumor mass, such as nasal obstruction, facial swelling/discomfort, diplopia, or headache.2 On the other hand, multiple cranial nerve palsy can be attributed to a variety of causes, such as infection, tumor, or vascular events. In 95% of these cases, the lesion causing the multiple cranial neuropathy can be seen intracranially.3 However, we describe herein a case of an extracranially located frontal sinus lymphoma.

A 42-year-old male patient presented with suddenly-developed right facial palsy at a local hospital. He had no specific medical or surgical history. The initial brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed no specific findings. He was thus treated with steroids under the impression of Bell's palsy, but showed no improvement. Over a one-month period, he then progressively developed symptoms of tinnitus in his right ear, dizziness, dysphagia, and sensory change on the right side of his face. He was then referred to our institution. At that time, MRI of the brain did not show any abnormalities. Laboratory work up, including complete blood count, was all in the normal range. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) profile was normal and there were no malignant cells. Steroid pulse therapy was initiated and partial resolution was observed, albeit temporarily. Four months later, the patient's symptoms gradually worsened and he developed right exophthalmus also. On physical examination, a House-Brackmann grade II facial palsy was observed. Both drums were intact. Nasal endoscopy demonstrated normal-looking mucosa without purulent discharge. Examination of the oral cavity and oropharynx showed a loss of the gag reflex of the right soft palate, but no tongue deviation. Vocal cord palsy was not seen. The patient also had difficulty elevating his right shoulder. There were no palpable cervical lymph nodes. Pure tone audiometric examination revealed that the patient had a high-tone sensorineural hearing defect in his right ear. Motor functions were normal. MRI revealed a mass involving the right frontal sinus (Fig. 1). Intranasal biopsy was performed, and histopathologic analysis revealed the mass to be diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and staining showed CD20, CD10, Bcl-2, and Bcl-6 to be diffusely expressed in the tumor cells (Fig. 2A-D). CD3, CD56, granzyme and TIA were not expressed. Ki-67 labeling index of the tumor cells was around 80% (Fig. 2E), while Epstein Barr virus-encoded RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization results were negative. Lymphoma staging with 1045positron emission tomography (PET) whole body scan showed increased F18-FDG uptake in the frontal sinus region and also in the liver. Liver involvement was later confirmed with an abdominal computed tomography scan. Serum lactate dehydrogenase levels were normal, and bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were negative. The patient was diagnosed with stage IV E DLBCL (Ann Arbor classification). Systemic chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) and intrathecal methotrexate was initiated in July, 2007. After 6 cycles, the patient's symptoms worsened and he subsequently received high-dose methotrexate, procarbazine and vincristine. The patient then underwent autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant in June, 2008. Since then, radiologic remission has been achieved, and the patient remains free of disease (follow up period: 50 months). Nearly all of the patient's neurologic symptoms have been resolved, but facial weakness can still be observed.

A review of the English-language literature revealed ten cases of primary frontal sinus lymphoma in five case reports4-8 and five case series.9-13 Two studies mentioned just the presence of one case of frontal sinus lymphoma each without further describing the patient in detail, and were not included in the summary. The other eight cases and our patient are summarized in Table 1. Of the eight patients where gender and age were described, the male-to-female ratio was 3 : 1, with the average age being 58.5 years. All eight cases except for ours presented with symptoms, resulting from the direct effect of the tumor mass. Facial swelling/bulging was the most common feature, being seen in six patients. Although not summarized in Table 1, frontal bone destruction/erosion was seen in all seven cases where the radiological findings were reported. All nine patients except for one who was not typed had Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of B-cell lineage. Most patients had a good prognosis, despite various stages, ranging from I to IV.

This patient was initially administered R-CHOP, but showed poor response. He ultimately had to receive autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Recent studies revealed that identification of MYC gene rearrangement may help determine those patients who can benefit from CHOP or CHOP-like regimens.14,15 Unfortunately, although this case showed signs of high-grade lymphoma on histological examination, gene rearrangement studies were not performed routinely at our institution at that time. If it had been determined, a different regimen might have been more beneficial to the patient.

Primary frontal sinus lymphoma patients usually present with symptoms which are directly due to the mass effect of the tumor, such as nasal obstruction, facial swelling/discomfort, or headache (Table 1). However, frontal sinus lymphoma in this case, presented with progressive multiple cranial nerve palsy. In this patient, it is postulated that the symptoms were due to leptomeningeal spread of the lymphoma, because there was no evidence of direct invasion. The neurological deficits were resolved once the lymphoma was treated. A large portion of multiple cranial nerve palsies arise from tumors, therefore, a clinical diagnosis of multiple cranial nerve palsy warrants searching for occult malignancy; systemic lymphoma with CNS involvement to be one of the diseases considered. Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion to prevent a late diagnosis. A delay in diagnosis results in more advanced stage at clinical presentation and a generally poor outcome. In this case, despite multiple medical consultations, the diagnosis of lymphoma remained elusive for five months. Due to the rarity of frontal sinus lymphoma, it is difficult to diagnose since there is no consensus on its presenting signs and symptoms. We found that most cases of frontal sinus lymphoma present with facial/ frontal swelling and show frontal bone destruction on imaging studies. We hope that raising awareness of this entity will allow clinicians to achieve a timely diagnosis, effective treatment, and consequently, a good prognosis.

Figures and Tables

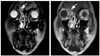

Fig. 1

Coronal MRI showing a mass in the frontal sinus. Left panel, T2 weighted image. Right panel, contrast-enhanced T1 weighted image. MRI, magnetic resonance image.

Fig. 2

Pathological results of intranasal biopsy of frontal sinus. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×100. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×400. (C) CD20 stain, ×200. (D) Bcl-2 stain, ×200. (E) Ki-67 stain, ×200.

Table 1

Literature Review of Primary Frontal Sinus Lymphomas

NHL, Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma; CTx, Chemotherapy; RTx, Radiotherapy; APBSCT, autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; ACOB, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, bleomycin, prednisone; CNS, central nervous system; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; NED, no evidence of disease; DOD, dead of disease.

*Not defined in article.

†Patient died before staging and treatment.

References

1. Fellbaum C, Hansmann ML, Lennert K. Malignant lymphomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1989. 414:399–405.

2. Vidal RW, Devaney K, Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Carbone A. Sinonasal malignant lymphomas: a distinct clinicopathological category. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999. 108:411–419.

3. Keane JR. Multiple cranial nerve palsies: analysis of 979 cases. Arch Neurol. 2005. 62:1714–1717.

4. Nemet AY, Deckel Y, Kourt G. Orbital invasion of frontal sinus lymphoma. Orbit. 2006. 25:149–151.

5. el-Hakim H, Ahsan F, Wills LC. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the frontal sinus: how we diagnosed it. Ear Nose Throat J. 2000. 79:738741–743.

6. Neves MC, Lessa MM, Voegels RL, Butugan O. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the frontal sinus: case report and review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005. 84:47–51.

7. Burres SA, Crissman JD, McKenna J, Al-Sarraf M. Lymphoma of the frontal sinus. Case report and review of literature. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984. 110:270–273.

8. Chain JR, Kingdom TT. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the frontal sinus presenting as osteomyelitis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007. 28:42–45.

9. Duncavage JA, Campbell BH, Hanson GA, Kun LE, Hansen RM, Toohill RJ, et al. Diagnosis of malignant lymphomas of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and nasopharynx. Laryngoscope. 1983. 93:1276–1280.

10. Cooper DL, Ginsberg SS. Brief chemotherapy, involved field radiation therapy, and central nervous system prophylaxis for paranasal sinus lymphoma. Cancer. 1992. 69:2888–2893.

11. Spiro JD, Soo KC, Spiro RH. Nonsquamous cell malignant neoplasms of the nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses. Head Neck. 1995. 17:114–118.

12. Hatta C, Ogasawara H, Okita J, Kubota A, Ishida M, Sakagami M. Non-Hodgkin's malignant lymphoma of the sinonasal tract--treatment outcome for 53 patients according to REAL classification. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2001. 28:55–60.

13. Shohat I, Berkowicz M, Dori S, Horowitz Z, Wolf M, Taicher S, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the sinonasal tract. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004. 97:328–331.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download