Abstract

Purpose

To discuss computed tomography (CT) evaluation of the etiology of vocal cord paralysis (VCP) due to thoracic diseases.

Materials and Methods

From records from the past 10 years at our hospital, we retrospectively reviewed 115 cases of VCP that were evaluated with CT. Of these 115 cases, 36 patients (23 M, 13 F) had VCP due to a condition within the thoracic cavity. From these cases, we collected the following information: sex, age distribution, side of paralysis, symptom onset date, date of diagnosis, imaging, and primary disease. The etiology of VCP was determined using both historical information and diagnostic imaging. Imaging procedures included chest radiograph, CT of neck or chest, and esophagography or esophagoscopy.

Results

Thirty-three of the 36 patients with thoracic disease had unilateral VCP (21 left, 12 right). Of the primary thoracic diseases, malignancy was the most common (19, 52.8%), with 18 of the 19 malignancies presenting with unilateral VCP. The detected malignant tumors in the chest consisted of thirteen lung cancers, three esophageal cancers, two metastatic tumors, and one mediastinal tumor. We also found other underlying etiologies of VCP, including one aortic arch aneurysm, five iatrogenic, six tuberculosis, one neurofibromatosis, three benign nodes, and one lung collapse. A chest radiograph failed to detect eight of the 19 primary malignancies detected on the CT. Nine patients with lung cancer developed VCP between follow-ups and four of them were diagnosed with a progression of malignancy upon CT evaluation of VCP.

Vocal cord paralysis may arise from neurogenic paralysis or mechanical fixation.1 It is sometimes the only sign of an underlying disease.2 Thus, it is clinically important to diagnose the primary disease in cases of vocal cord paralysis (VCP) because many of its potential causes, such as symptom-free malignant tumors, can be fatal or cause serious morbidity if detected late.2,3 Radiologic evaluation is often useful for determining the etiology of VCP, especially for conditions within the thoracic cavity. However, chest radiographs can sometimes miss small lesions in the mediastinum.2 In these cases, computed tomography (CT) can be a valuable diagnostic tool. We have found only a few original reports on CT evaluation of VCP for thoracic disease.2,4 In this article, we performed a retrospective CT analysis of our patients in order to review cases of VCP with an underlying etiology of thoracic disease.

The study was approved by the institutional review board. We retrospectively reviewed 115 cases of VCP with CT evaluation from patient records at our hospital among cases occurring any time from January 2000 to March 2010. We separated out the cases where VCP was caused by an underlying thoracic disease (a total of 36 patients; 23 male and 13 female) and patient data such as age, distribution, side of paralysis, symptom onset date, date of diagnosis, diagnostic imaging studies, and primary disease was extracted from each case.

After the general and otolaryngologic examinations, laryngeal fiberscopy was performed for all new patients with VCP to examine the state of paralysis and to look for the presence of a primary lesion in the larynx or hypopharynx. The etiology of VCP was determined using both historical information and diagnostic imaging. Imaging procedures included a chest radiograph, a CT of the neck or chest, and esophagography or esophagoscopy.

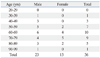

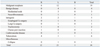

CT was used in 115 patients with VCP. In the majority of cases, VCP was unilateral (Table 1). One hundred and five (91.3%) patients were identified as having unilateral VCP, of whom 59 were male and 46 were female. Of the 105 unilateral cases of VCP, 73 cases had left-side and 32 had right-side paralysis. Ten (8.7%) patients were identified as having bilateral VCP, of whom four were male and six were female.

Our analysis found that 70 (60.9%) of the 115 patients with VCP had an identified cause, and 45 (39.1%) were idiopathic. Furthermore, in 36 (31.3%) of the 115 patients, VCP was caused by chest diseases, and in 34 (29.6%) VCP was caused by neck diseases. A summary of the identified underlying etiologies of VCP is shown in Table 2.

Of the 36 patients whose VCP had a thoracic pathology, nine patients underwent only a neck CT, seven had only a chest CT, and 20 underwent both neck and chest CT scans.

Of the 36 patients with thoracic disease, the majority were in their 6th decade of life, 23 (63.9%) were men, and 13 (36.1%) were women. The sex and age distributions of the VCP patients with thoracic disease are shown in Table 3. The duration of VCP symptoms varied widely, ranging from two days to 30 years.

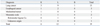

The diagnostic categories of the primary thoracic diseases identified among patients presenting with VCP are shown in Table 4. Thirty-three of 36 patients with thoracic diseases had unilateral VCP, 21 (63.6%) had left-side paralysis, and 12 (36.4%) had right-side paralysis. Of the primary thoracic diseases, malignancy was the most common (19 cases, 52.8%). Eighteen (94.7%) cases of 19 malignant diseases had unilateral paralysis, 12 (66.7%) had left-side paralysis, and six (33.3%) had right-side paralysis (Fig. 1).

Seventeen (47.2%) of the 36 patients with thoracic disease were found to have a non-malignant condition within the thoracic cavity that accounted for their VCP. Tuberculosis was the second most common primary chest disease causing VCP (six cases, 16.7%). We found five cases of inactive tuberculosis and one case of active apical tuberculosis (Fig. 2).

One case of VCP was caused by aortic arch aneurysm. One case involved neurofibromatosis associated with left VCP, and five cases of VCP were caused by iatrogenic injury (Fig. 3).

The causes of bilateral VCP (n=3) were caused by lung cancer (n=1), pulmonary tuberculosis (n=1) and injury from a tracheostomy procedure (n=1).

The malignant tumor types detected by CT and side distribution of the VCP are shown in Table 5. Of the detected malignant tumors in the chest, lung cancer was the most common (13, 68.4%). The other malignancies were three (15.8%) cases of esophageal carcinoma, two (10.5%) cases of metastatic tumors, and one (5.3%) case of mediastinal tumor.

Of the 12 patients diagnosed with a malignancy who presented with left VCP, we discovered direct cancer invasion into the left recurrent laryngeal nerve in three cases, all of whom were diagnosed with lung cancer, and metastasis to the lymph nodes in nine cases (six cases of lung carcinoma, two cases of esophageal carcinoma, and one case of unknown metastasis). Of the six patients diagnosed with a malignancy who presented with right VCP, we found direct cancer invasion into the right recurrent laryngeal nerve in two cases; among these, one case was diagnosed as apical lung carcinoma, and the other case was diagnosed as a superior mediastinal tumor. In the other four patients, metastasis to the either the right highest mediastinal or the right supraclavicular lymph node was found in three cases, and metastasis was found in both sites in one case. In the only patient diagnosed with a malignancy who presented with bilateral VCP, lung cancer was detected in the right upper lobe, with metastasis to the bilateral lymph nodes.

Nine patients with lung cancer developed VCP between follow-ups and four of them were diagnosed with progression of lung cancer after CT evaluation of VCP (Fig. 4). One of the patients with lung cancer who presented with VCP had a left lung collapse due to an enlarged mass in the left hilum, but there was no evidence of metastatic nodes, or of a mass in the aortopulmonary window or near the pathway of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve. So we concluded that VCP was probably caused by the effect of pressure on the nerve from the collapsed lung and classified the patient under the miscellaneous group instead of the lung cancer group in Table 4.

The malignant chest lesions were clearly detectable with contrast-enhanced chest CT or neck CT in all 19 cases. However, a chest radiograph failed to detect the primary lesions in eight cases (Fig. 5).

Of the 36 patients with chest diseases, nine patients underwent an esophagography or esophagoscopy. Of these nine patients, seven were male, and two were female; four had right-side VCP, and five had left-side VCP. Of the nine patients with an esophagography or esophagoscopy, six had no abnormalities, and three had esophageal cancer (two left-sided VCP cases and one right-sided VCP case). The esophagography was able to detect all three esophageal cancers, and the CT scans also revealed them in all three cases.

The recurrent laryngeal nerves innervate the vocal cords. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve leaves the vagus nerve at the anterior surface of the right subclavian artery and runs inferiorly, looping around the subclavian artery, then ascends medially in the tracheoesophageal groove. The left recurrent nerve branches more caudally from the vagus nerve on the anterior surface of the aortic arch. It passes inferiorly around the arch through the aortopulmonary window to ascend in the tracheoesophageal groove. Both recurrent laryngeal nerves are intimately associated with the thyroid gland.4

In the thorax, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is more vulnerable than the right because it pursues a longer intrathoracic course, coming into contact with the mediastinal surface of the left lung, continuing along the mediastinal lymph nodes, and finally looping around the aortic arch.5 VCP has been reported to be about 1.4-2.5 times more frequent on the left side than on the right.3 In our cases diagnosed with a thoracic disease, left-side VCP was 1.75 times more frequent than right-side VCP.

The function of the recurrent laryngeal nerve can be disrupted by pressure or by injury of the nerve caused by disease pathology invading the nerve.5 Malignant invasion of the vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerves can also occur with thyroid neoplasms, carcinoma of the lung, esophageal carcinoma, and metastases to the mediastinum.6,7 Earlier studies found that tumors were the most frequent cause, and of these tumors, bronchogenic carcinoma was the most common cause of unilateral VCP, as can be seen from our results.7-9

In patients with lung carcinoma, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is most frequently involved as it courses through the aortopulmonary window.4 In our study, 12 of 19 VCP patients with a malignant chest neoplasm had left-side VCP, and nine of 13 VCP patients with lung carcinoma had left-side VCP.

Left VCP associated with a mass in the lung is usually of sinister significance, implying a lung carcinoma with subaortic lymph node metastasis.10 In our patients with left-side paralysis, six of nine patients with lung carcinoma showed metastasis to a subaortic lymph node, and three of them showed direct tumor invasion of the aortopulmonary window.

However, right-side mediastinal adenopathy extending cephalad to the region of the right subclavian artery can also involve the right recurrent laryngeal nerve. In addition, patients with a superior sulcus tumor can develop right-side VCP when the tumor extends into the supraclavicular space.4 The right recurrent laryngeal nerve hooks around the first part of the subclavian artery and is related only to the apex of the right lung.5 Of the six patients with malignant tumors and right-side VCP, we found direct tumor invasion of the nerve in two and metastasis to the highest mediastinal or supraclavicular lymph node in three cases.

The diagnostic approach used to evaluate patients presenting with VCP differs among otolaryngologists, and no consensus has been achieved regarding the appropriate initial workup of these patients. Although no precise evaluation sequence exists, a thorough history and physical examination reveal the etiology in the majority of cases. Previously, radiologic examination of patients with extralaryngeal causes of VCP included chest and skull radiographs, barium esophagography, and a thyroid scan.4 With the advent of advanced studies of the head and neck [CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)], it is now possible to image the entire course of the laryngeal nerves. These imaging methods obviate the need for tests such as thyroid scans, thyroid function tests, skull radiographs, and barium esophagography.9 The probability of an isolated laryngeal motor nerve encased by an intracranial lesion is highly unlikely due to the relationship of the corticobulbar fibers to the surrounding structures. Thus, brain MRI or CT is not recommended unless signs or symptoms suggest an intracranial lesion.11

The most important objective in evaluating a patient with VCP is to exclude the existence of a treatable and potentially life-threatening primary disease as the cause of VCP.9 Chest radiograph remains a useful screening study, but, it is not sufficient for the full evaluation of VCP.11 Because it is very important to scrutinize the mediastinum, particularly the aortopulmonary window and the paratracheal region in patients with VCP,2 further diagnostic imaging may be needed.

The CT images analyzed in this study demonstrated that in a patient presenting with VCP, CT can more accurately detect the extent and location of the responsible pathology than a chest radiograph. We found that of the 19 CT-detected malignant neoplasms, eight were not detected on the chest radiograph. Five of them were associated with left-side paralysis and showed a metastatic node in the aortopulmonary window on CT. The other three were associated with right-side paralysis, and the CT scan detected one case of right apical lung carcinoma and two cases of metastatic nodes in the right upper paratracheal region. Masaki, et al. suggested that neck ultrasonography and chest X-rays were a sufficient evaluation modality for patients with right VCP.3 But in our study, CT was needed in a patient with a small right apical lung carcinoma that was hidden behind rib shadows, and also in a patient with VCP caused by phlebitis and right upper mediastinitis during use of an intravenous chemo port (an implantable port for chemotherapy). We do not recommend a routine chest radiograph for evaluating the etiology of VCP caused by thoracic diseases.

The CT scan is a very sensitive study for lesions in the neck and upper chest. Furthermore, it is now available at a moderate cost.9 Nevertheless, a chest CT scan was not routinely taken in this study. We discovered that when neck CT scans were taken for patients with right VCP, including an area of the skull base to the thoracic inlet, and for left VCP, including the area up to the aortic triangle, most primary diseases in the chest were detectable. Therefore, it might be cost effective to scan down to the level of the aortic triangle when taking neck CT scans for VCP patients, regardless of the paralytic side.

However, in certain situations, an additional chest CT is also required. When cancer is found in the neck CT, an additional chest CT scan is needed to evaluate the extent and stage of the malignancy. An additional chest CT scan is also warranted when the neck CT shows an enlarged aortopulmonary window, supraclavicular nodes, or right highest mediastinal nodes without a definite primary malignancy focus, such as mid to low esophageal cancer or lung cancers that are outside the boundaries of the neck CT scan. Thus, we recommend taking both neck and chest CT scans at the first visit.

For males, when no primary malignancy is found on the CT scans, contrast esophagography or esophagoscopy is recommended to examine the possibility of esophageal cancer.3 Esophagoscopy has the advantage of tissue visualization and biopsy. It is not necessary to perform contrast esophagography or esophagoscopy as an initial diagnostic tool in female patients with VCP, as esophageal cancer is rarely the cause of VCP in females.3 Our study revealed similar results in that all three esophageal carcinoma patients were male. A marked sex difference exists in the origin of malignant tumors. In addition to esophageal carcinoma, the incidence of lung cancer is higher in males with VCP.3 In our study, we also found similar results, with 11 of 13 lung cancers being found in men.

Acquired cardiovascular disease such as cardiomegaly, pulmonary hypertension, aortic arch aneurysm, right subclavian aneurysm, ductus arteriosus aneurysm, or an enlarged left atrium may compress or stretch the left recurrent laryngeal nerve.12-17 We experienced a case of VCP caused by aortic arch aneurysm.

Left recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy in a patient with mediastinal lymphadenopathy caused by tuberculosis, pneumoconiosis, or sarcoidosis has rarely been reported.18 In chronic pulmonary disease, paralysis may be caused by three possible mechanisms that exert effects on the nerve: 1) the nerve is passing through or is adjacent to a mass of caseating nodes, 2) the nerve is trapped in the dense fibrous pleural thickening or in the chronic fibrosing mediastinitis that may occur, and 3) the nerve is being stretched due to retraction of the left upper lobe bronchus pulled towards the apex.19 We found five cases of patients with tuberculosis-destroyed lungs or tuberculous pleurisy scars including the upper mediastinal pleura who had a history of VCP for 4-30 years (mean 14 years). The probable mechanism in these cases would be mechanisms 2) and 3) noted above. We also found a patient with active tuberculosis in the apex. The mechanism in this case was uncertain, but other factors are possible, such as the direct spread of infection, damaging the nerve. Tuberculosis, with six cases, was the second most common cause of VCP in our study, following the most common cause, malignant neoplasm, with 19 cases. These results are similar to those of a report by Titche.5

Intrathoracic vagus nerve sheath tumors have also been reported.20 We also encountered a case of neurofibromatosis with multiple neurofibroma masses, including in the aortopulmonary window, causing left-side VCP.

Vocal cord paralysis can occur after resection of a thoracic aortic aneurysm, carotid endarterectomy, parathyroidectomy, radical neck dissection for thyroid carcinoma, thoracic esophagectomy, mitral valve replacement, tracheostomy or intubation.21,22 In our cases, VCP associated with surgery or trauma occurred only after tracheostomy (n=2), chemo port insertion (n=1), surgery for lung cancer (n=1), and surgery for esophageal cancer (n=1).

The etiologies of bilateral VCP in adults are 1) following thyroidectomy, which is the most common reason; 2) various neurogenic diseases, such as poliomyelitis, Parkinson's disease, cerebrovascular accident, multiple sclerosis, etc.; 3) malignancy of the neck and mediastinum, such as in our case diagnosed with right lung cancer with bilateral metastatic nodes; and 4) many others, including foreign bodies, intubation, bilateral neck dissection, infection, congenital lesions, trauma, and idiopathic paralysis.23 In our study, we found a case of bilateral VCP caused by bilateral upper lobe tuberculosis, another by tracheostomy, and a third by lung cancer.

Although a CT scan is important, the history of the patient is also essential under the following circumstances: 1) VCP in a patient during follow-up for a known malignancy, as it may indicate recurrence or aggravation of the primary lesion; 2) VCP after tracheostomy, chemo port insertion, or an operation on the lung or esophagus, which suggests the possibility of iatrogenic paralysis; and 3) a 10- to 30-year history of VCP, which may indicate VCP caused by tuberculosis.

A negative CT in both the chest and neck reassures clinicians that the VCP is idiopathic in origin, thus obviating the need for aggressive therapeutic regimens or further invasive diagnostic testing.4 Among our cases, 39.1% were idiopathic.

Among the patients who presented to an otolaryngologist with VCP as the initial sign, the frequency of detection of a malignant tumor as the primary lesion is relatively high. Hence, it is clinically important to diagnose the primary disease in cases of VCP.3 Identifying the cause of VCP can benefit the patient through early detection and treatment of a malignant mass, help recognize recurrence or aggravation of the primary malignancy, or identify metastasis. In our study, nine patients with lung cancer developed VCP during the periods between follow-up appointments and four of them were subsequently diagnosed with lung cancer progression. Radiologic imaging is also needed to differentiate between various non-malignant causes of VCP. To determine the etiology of VCP caused by thoracic diseases, we recommend both neck and chest CT scans and in some cases, esophagography or esophagoscopy, especially for males.

Figures and Tables

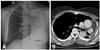

Fig. 1

A 72-year-old woman with a paralyzed left vocal cord. Contrast-enha-nced CT demonstrates a large lung cancer in the left upper lobe with invasion in the aorticopulmonary window (arrows). CT, computed tomography.

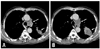

Fig. 2

A 61-year-old woman with a paralyzed left vocal cord for 11 years. (A and B) Chest radiograph (A) and contrast-enhanced CT (B) show the left lung destroyed from pulmonary tuberculosis with a marked decrease in lung volume and a mediastinal shift to the left. Fibrocalcific tuberculous scars can be seen in the right upper lobe. CT, computed tomography.

Fig. 3

A 73-year-old woman with a paralyzed right vocal cord after failure of a chemo port insertion. (A and B) Contrast-enhanced CT scans demonstrate cellulitis in the right anterior chest wall along the tract of a previous chemo port (arrows) (A) and right upper mediastinitis (arrows) (B). CT, computed tomography.

Fig. 4

A 73-year-old man with paralyzed left vocal cord. (A) Contrast-enhanced CT prior to vocal cord paralysis demonstrates an irregular lung cancer (short arrow) in the apicoposterior segment of the left upper lobe and conglomerated metastatic nodes (long arrow) in the aortopulmonary window. (B) Follow-up CT after development of left vocal cord paralysis shows enlargement of a lung cancer (short arrow) and metastatic nodes in the aortopulmonary window (long arrow). CT, computed tomography.

Fig. 5

A 61-year-old man with a paralyzed right vocal cord. (A) Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates a small irregular lung cancer in the right apex (white arrow) and a metastatic node in the right upper paratracheal region (black arrow). (B) Retrospective review of chest radiograph suggests a hidden mass being overlapped by the medial end of the right first rib (arrow). CT, computed tomography.

References

1. Benninger MS, Gillen JB, Altman JS. Changing etiology of vocal fold immobility. Laryngoscope. 1998. 108:1346–1350.

2. Bando H, Nishio T, Bamba H, Uno T, Hisa Y. Vocal fold paralysis as a sign of chest diseases: a 15-year retrospective study. World J Surg. 2006. 30:293–298.

3. Furukawa M, Furukawa MK, Ooishi K. Statistical analysis of malignant tumors detected as the cause of vocal cord paralysis. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1994. 56:161–165.

4. Glazer HS, Aronberg DJ, Lee JK, Sagel SS. Extralaryngeal causes of vocal cord paralysis: CT evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983. 141:527–531.

6. Evans JM, Schucany WG. Hoarseness and cough in a 67-year-old woman. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2004. 17:469–472.

7. Chen HC, Jen YM, Wang CH, Lee JC, Lin YS. Etiology of vocal cord paralysis. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2007. 69:167–171.

8. de Gandt JB. [Recurrent nerve compression]. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1970. 24:520–554.

9. Terris DJ, Arnstein DP, Nguyen HH. Contemporary evaluation of unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992. 107:84–90.

10. Sherani TM, Angelini GD, Passani SP, Butchart EG. Vocal cord paralysis associated with coalworkers' pneumoconiosis and progressive massive fibrosis. Thorax. 1984. 39:683–684.

11. Altman JS, Benninger MS. The evaluation of unilateral vocal fold immobility: is chest X-ray enough? J Voice. 1997. 11:364–367.

12. Camishion RC, Gibbon JH Jr, Pierucci L Jr. Paralysis of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve secondary to mitral valvular disease. Report of two cases and literature review. Ann Surg. 1966. 163:818–828.

13. Che GW, Chen J, Liu LX, Zhou QH. Aortic arch aneurysm rupture into the lung misdiagnosed as lung carcinoma. Can J Surg. 2008. 51:E91–E92.

14. Bin HG, Kim MS, Kim SC, Keun JB, Lee JH, Kim SS. Intrathoracic aneurysm of the right subclavian artery presenting with hoarseness: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2005. 20:674–676.

15. Kokotsakis J, Misthos P, Athanassiou T, Skouteli E, Rontogianni D, Lioulias A. Acute Ortner's syndrome arising from ductus arteriosus aneurysm. Tex Heart Inst J. 2008. 35:216–217.

16. Gothi R, Ghonge NP. Case Report: Spontaneous aneurysm of ductus arteriosus: A rare cause of hoarseness of voice in adults. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2008. 18:322–323.

17. Morgan AA, Mourant AJ. Left vocal cord paralysis and dysphagia in mitral valve disease. Br Heart J. 1980. 43:470–473.

18. el-Kassimi FA, Ashour M, Vijayaraghavan R. Sarcoidosis presenting as recurrent left laryngeal nerve palsy. Thorax. 1990. 45:565–566.

19. Fowler RW, Hetzel MR. Tuberculous mediastinal lymphadenopathy can cause left vocal cord paralysis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983. 286:1562.

21. Barondess JA, Pompei P, Schley WS. A study of vocal cord palsy. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1986. 97:141–148.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download