INTRODUCTION

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is often caused by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) serogroup strains, mainly Escherichia coli O157:H7. Recently, non-O157:H7 serotypes of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli have been isolated, although the majority of outbreaks and sporadic cases in humans have been associated with serotype O157:H7.1,2 In 1998, the isolation of an Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain from a hemolytic uremic syndrome patient was first reported in Korea.3 Thereafter, non-O157:H7 EHEC infections associated with HUS have been reported,4 but EHEC O104:H4 infections have not yet been reported in Korea.

We report the first case of Escherichia coli O104:H4 associated HUS successfully treated with plasma exchange and hemodialysis in Korea.

CASE REPORT

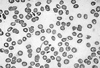

A 29-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. She was previously healthy and had no specific past medical history. Stool culture was performed and she received intravenous hydration. On hospital day 2, her urine volume decreased, and generalized edema developed. She was transferred to Chonnam National University Hospital (CNUH). Upon admission her blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg, pulse rate was 72/min, respiration rate was 32/min, and body temperature was 36.6℃. The abdomen was slightly tender but not distended. Laboratory tests showed a serum creatinine of 4.2 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen of 35.4 mg/dL, hemoglobin 9.2 g/dL, platelet count 19,000/mm3, corrected reticulocyte count 5.4%, lactate dehydrogenase 3150 IU/L, haptoglobin 7.69 mg/dL, total bilirubin 1.31 mg/dL, and direct bilirubin 0.19 mg/dL. Peripheral blood smear showed microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (Fig. 1). A diagnosis of HUS was made based on the occurrence of acute renal failure, hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Escherichia coli O104:H4 was identified in the stool culture performed at the hospital where she was first admitted by using polymerase chain reaction for virulence-associated genes of EHEC, but other EHEC related serogroups including Escherichia coli O157:H7 were not found at Chonnam Institute of Health and Environment. She received hemodialysis for four days, and plasma exchange and fresh frozen plasma for two weeks. On hospital day 14, tonic seizure occurred suddenly but was not presented until the following day. The brain computed tomography (CT) and electroencephalogram (EEG) did not show any abnormalities. On hospital day 20, her platelet count rose to 299,000/mm3, hemoglobin rose to 10.6 g/dL, reticulocyte count dropped to 1.5%, lactate dehydrogenase dropped to 507 IU/L, and blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine fell to 17.5 mg/dL and 1.0 mg/ dL, respectively. Peripheral blood smear did not show evidence of hemolytic anemia. After hospital day 21, two successive stool specimens yielded negative results for Escherichia coli O104:H4. On hospital day 27, she was discharged and received follow-up care as an outpatient.

DISCUSSION

The pathotypes of intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli are classified as follows : Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC)/enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC), enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC), enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC), and diffusely adherent Escherichia coli (DAEC). STEC/EHEC strains can cause hemorrhagic colitis and HUS. EHEC O157:H7 has since been documented as the cause of both large outbreaks and sporadic infections in the United States and around the world. Several large outbreaks resulted from the consumption of undercooked ground beef and other foods. Our patient frequently ate fast food, particularly hamburgers. We could not exclude the possibility that EHEC O104:H4 was transmitted by contaminated hamburger consumed by our patient. However, we did not investigate the origins of the EHEC O104:H4 infection Hemorrhagic colitis associated with EHEC O157:H7 and others is characterized by grossly bloody diarrhea, often with remarkably little fever or inflammatory exudate in the stool. Although the diarrheal illnesses have been self-limiting, a significant number of children and adults have subsequently developed a potentially fatal hemolytic uremic syndrome or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.5 The clinical manifestations of post-diarrheal HUS include renal failure, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Several studies reported that the culture rate of EHEC O157:H7 was 2% to 51% in post-diarrheal HUS.6 HUS complicates 10% of bloody diarrhea induced by EHEC. Some estimate that EHEC causes at least 70% of post-diarrheal HUS in the United States and that 80% of these are caused by EHEC O157:H7, and the other 20% by a different serotype of EHEC.7,8 In Australia, however, EHEC O157 infections are rare in patients with post-diarrheal HUS and the majority are caused by non-O157 EHEC. The use of antimotility agents in children under 10 years of age or in elderly patients should be avoided as it increases the risk of HUS with EHEC infections. The incubation period has usually been 3 to 5 days after bloody diarrhea, but HUS infrequently develops no prodromal symptom.9 Although the illness is usually self-limited, the mortality rate is 3% to 5% in young children and 30% of patients with HUS develop permanent renal failure, hypertension or neurologic sequelae.10

Escherichia coli serotype O104:H21 infections were documented in the United States, and other EHEC O104:(H-, H2, H7, H21) infections were also reported in several countries.11-14 However EHEC O104:H4 associated HUS has not yet been reported. EHEC O104 associated HUS has not yet been reported in Korea. So this is the first description of EHEC O104:H4 associated HUS in Korea. EHEC O104:H4 produces a shiga-like toxin (verocytotxin) that may cause direct renal and endothelial cell damage and may adhere to intestinal epithelium resulting in bloody diarrhea. Thrombocytopenia occurs as a consequence of platelet consumption, and hemolytic anemia results from intravascular fibrin deposition, increased red blood cell fragility, and fragmentation. 15

Plasma exchange, which removes the plasma with the shiga-like toxin and its breakdown products, may decrease the effects of the toxin. This may be more effective than plasma infusion alone.16 In 1996, an outbreak of EHEC O157:H7-related HUS demonstrated the potential efficacy of plasma exchange in reducing mortality in the elderly; 83% of those who did not have a plasma exchange died compared with 31% who did receive plasma exchange.17

Although the role of plasma exchange in HUS secondary to EHEC infection remains controversial,18 we suggest that plasma exchange may improve the outcome in adult bloody diarrhea-associated HUS. We also recommend that shiga toxin producing bacterial infections including EHEC O157:H7 and O104:H4 must be considered in all bloody diarrhea prodrome HUS patients.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download