Abstract

Although congenital renal tumors are rare, congenital mesoblastic nephroma (CMN) is the most common renal tumor in early infancy. It is non-metastatic, well differentiated, amenable to surgical removal, and carries a good prognosis. Polyhydramnios has been detected in most of the published cases of CMN. However, we experienced a rare case of fetal CMN associated with oligohydramnios. A 28-yr old woman at 34 weeks of gestation was referred to our hospital for oligohydramnios and a fetal abdominal mass. An ultrasonography revealed a huge, well-encapsulated mass arising from the right kidney. An emergency cesarean section was performed due to fetal distress. After birth, despite intensive neonatal care, the baby died because of renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, pulmonary edema, together with other problems

Congenital mesoblastic nephroma (CMN) is the most common renal solid tumor of the newborn period (1). CMN occurs in two forms: a typical or leiomyomatous benign type seen almost exclusively in infants under the age of three months and an atypical or cellular type usually seen in older children, but also occurring in infants. The latter type is potentially malignant and capable of recurrence and metastasis (2). Mixed forms with a combination of the two patterns have also been reported (3). CMN is associated with polyhydramnios in most cases, and surgical excision is almost always curative (4-8). Although CMN has a good prognosis, rare cases of CMN that show oligohydramnios resulting from fetal renal failure may be difficult to diagnose accurately and such patients have a poor prognosis due to the destruction of homeostasis. We report a case of a congenital mesoblastic nephroma that presented with oligohydramnios, which was detected by ultrasonography in the prenatal period. Early and accurate prenatal diagnosis of a renal tumor may improve the outcome of affected pregnancies by allowing for prompt implementation of the best strategy for prenatal management and delivery (9). The differential diagnosis of mesoblastic nephroma includes hydronephrosis, focal renal dysplasia, multicystic dysplastic kidney, malignant nephroblastoma, Wilms' tumor, diffuse nephroblastomatosis, and infantile polycystic kidney disease (4, 5, 10-12). Accurate prenatal ultrasonography can give diagnostic information useful for the detection of CMN.

A 28-yr old woman, gravida 2, para 1, was referred to our hospital at 34 weeks of gestation for oligohydramnios and a fetal abdominal mass detected by ultrasonography. An earlier delivery had been performed by cesarean section, due to breech presentation. The results of routine pregnancy tests (CBC, U/A, viral marker, Toxoplasma, and others) were non-specific and the triple test indicated that the patient was not at high risk. At 24 weeks of gestation, ultrasonographic findings showed a fetal weight (650 g) appropriate for the menstrual dates, no fetal abnormality, and adequate amniotic fluid. After the checkup, the patient did not receive antenatal care for two months. At 33 weeks of gestation, the patient returned to the local clinic where a fetal abdominal mass and a low level of amniotic fluid were noted. The fetus was suspected the intrauterine growth restriction (1,440 g, below 10% of 33 weeks of gestation), and the patient was referred to our hospital. On admission, her vital signs were as follows; temperature 36.0℃, pulse rate 84/min, respiration rate 20/min, and blood pressure 120/80 mmHg. Laboratory findings were not remarkable. An indicated sonography (using Aloka SSD-5000) was performed. The amniotic fluid index was almost zero. A huge (8.1×5.0×7.7 cm), well-encapsulated, abdominal mass was detected, which was composed of both solid and multiple cystic components (Fig. 1). The tumor arose from the right fetal kidney, while the left kidney and other fetal organs were normal. Upon fetal heart rate monitoring, repeated severe variable deceleration was noted, and an emergency cesarean section was performed. A female neonate weighing 1,750 g, with Apgar scores of 5 at 1 min and 9 at 5 min, was delivered. The pH value of umbilical arterial blood was 7.319.

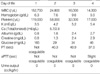

On admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, the vital signs of the neonate were as follows; temperature 36.5℃, pulse rate 138/min, respiration rate 62/min, and blood pressure 69/43 mmHg. On physical examination, the infant showed a remarkable abdominal mass 8 cm in diameter in the right side of the abdomen. The mass was almost occupying the abdominal cavity. The infant also had clubbed feet. Ultrasonographic examination (using GE Logiq 9) and computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed a well circumscribed, heterogeneous, non-enhanced mass 7 cm in diameter, originating from the right kidney, which showed both necrotic and cystic components. The left kidney was normal (Fig. 2, 3). Within 24 hr of birth, the infant developed anuria, severe anemia, hypoglycemia, and hypoalbuminemia. Prothrombin time and activated prothrombin time were both prolonged. Despite intensive treatment, no urine was ever excreted and both generalized and pulmonary edema developed. On the second day, gastrointestinal hemorrhage and hypotension developed. The infant was resuscitated and intubated. Due to the simultaneous presence of several severe systemic conditions, radical nephrectomy could not be performed. The laboratory findings showed general deterioration. Renal failure developed and hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and poor coagulation profiles (aPTT undetectably prolonged) could not be corrected despite major therapeutic interventions. (Table 1). The infant died at four days of age, owing to respiratory failure and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

Autopsy was performed and revealed an encapsulated mass, with dimensions 8.5×8.0×5.0 cm arising from the right renal pelvis. Cystic hemorrhage was observed (Fig. 4). On the side of the mass, a remnant of the kidney, with dimensions 2.0×0.8×2.0 cm, was seen. On cross section, the mass was yellow to pink in color, and lobulated. The left kidney and both lungs were normal. Microscopically, the tumor was classified as a cellular mesoblastic nephroma (Fig. 5). The neonate's karyotype was normal (46, XX).

CMN is the most common renal tumor in infancy, accounting for 3-6% of all childhood renal masses and 50% of all solid tumors in the neonatal period (13). Current opinion favors the classification of mesoblastic nephroma as a distinct, and usually benign neoplasm, arising from the renal parenchyma (14). There appears to be a higher incidence of preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes in pregnancies complicated by CMN, as a result of associated polyhydramnios (4, 15). However, the mechanism of polyhydramnios is unclear (16). Postulated mechanisms include a decreased gastrointestinal uptake due to compression by the lesion and increased renal perfusion resulting in increased urine production. Another mechanism, hypercalcemia induced polyuria of the fetus, has been reported secondary to the tumor secretion of prostaglandin. Hypercalcemias have been reported to be caused by the tumor secretion of prostaglandin. Hypertension may also occur and may be caused by entrapment of renal parenchyma by invading fibrous strands at the edge of the tumor with resultant renin hypersecretion (2).

Pathologically, the tumor has two patterns. The classical pattern of CMN is a moderate cellular proliferation of thick interlacing bundles of spindle cells, with elongated nuclei, which usually infiltrate into the renal and perirenal tissues. Mitotic figures are present usually in the range of 0 to 1 per 10 high power fields (17). The other pattern, termed cellular mesoblastic nephroma, is more common, and consists of densely cellular proliferation of polygonal cells with mitotic figures in the range of 8 to 30 per 10 high power fields (17). Cysts are common in this pattern.

Sonographically, mesoblastic nephroma may present as a large (4 to 8 cm), unilateral renal mass with nodular densities, or as diffuse renal enlargement. These tumors are predominantly solid, but cystic areas are occasionally seen (18). Unlike Wilms' tumor, there is no well-defined capsule, most likely due to hemorrhage with subsequent cystic degeneration (19). Patients suffering from CMN may show abnormalities in systems not closely associated with the tumor. Such abnormalities may include neuroblastoma (20), central nervous system defects (5, 20), genitourinary problems, gastrointestinal difficulties, and limb abnormalities (5). Radical resection of the tumor is the treatment of choice, which is usually curative (15). However, a small percentage of patients with these tumors experience local recurrence or distant metastasis due to inadequate resection (21) or cellular or atypical CMN, which is potentially a malignant tumor (3, 22). No familial or exogenous factors have been correlated to CMN occurrence, in contrast to the development of Wilms' tumor, for example, where a familial link has been noted. There is no known predisposition to its occurrence in siblings born to the same mother after the birth of an affected infant. The condition is not associated with other karyotypic abnormalities (15). Cytogenetic abnormalities such as trisomy 11 occur sporadically (23, 24). However, Fuchs et al. reported a case of CMN occurring in two siblings within one family and suggested that a second-trimester anomaly scan with targeted examination of the kidneys is warranted in families with a child affected by CMN (25).

In our case, the pregnant patient presented with oligohydramnios, and the neonate showed anuria, hypotension, hyperkalemia, abnormal coagulation profiles, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and other pathologic findings. An associated anomaly noted was clubbed feet. On autopsy, the tumor was shown to be a cellular mesoblastic nephroma with mitotic figures more than 8 per 10 high power fields. Areas of coagulative necrosis and hemorrhage were also observed.

According to the literature, polyhydramnios was observed in almost 40% of the CMN cases (20), and acute fetal distress occurred in 25% of fetuses with CMN (26). Even though it is important to note the high incidence of polyhydramnios (24), CMN can also be accompanied by oligohydramnios, which heralds a poor prognosis. Careful, continuous observation of the fetus should be considered when a renal tumor is diagnosed on routine prenatal ultrasound, and close ultrasound follow-up and maternal-fetal monitoring should be performed to detect any fetal complications.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Prenatal ultrasound reveals a well-encapsulated abdominal mass with dimensions 8.1×5.0×7.7 cm.

Fig. 2

Postnatal ultrasound reveals a huge, well circumscribed, echocomplex mass, possibly arising from the right kidney.

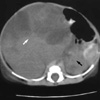

Fig. 3

Contrast-enhanced CT of right renal tumor. The CT scan shows a well circumscribed, heterogeneous, non-enhanced mass with dimensions 7.5×5.0×7.4 cm, developed from the right kidney, with both necrotic and cystic components (white arrow). The left kidney was normal (black arrow).

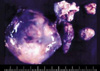

Fig. 4

Gross photograph shows the encapsulated mass with dimensions 8.5×8.0×5.0 cm arising from the right renal pelvis.

Fig. 5

(A) The section revealed a well-defined cellular mass (Hematoxylin-eosin stain,×40). (B) The tumor showed proliferation of spindle cells with short-elongated nuclei with necrosis and numerous mitotic figures (inset) (Hematoxylin-eosin stain, ×200). (C) In some areas, the tumor cells were haphazardly arranged. Entrapped immature glomeruli were often present in the tumor (Hematoxylin-eosin stain, ×200).

References

3. Bisceglia M, Carosi I, Vario M, Zaffarano L, Creti G. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma: report of a case with review of the most significant literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2000. 196:199–204.

4. Giulian BB. Prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis of fetal renal tumors. Radiology. 1984. 152:69–70.

5. Walter JP, McGahan JP. Mesoblastic nephroma: prenatal sonographic detection. J Clin Ultrasound. 1985. 13:686–689.

6. Howey DD, Farrell EE, Sholl J, Goldschmidt R, Sherman J, Hageman JR. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma: prenatal ultrasonic findings and surgical excision in a very-low-birth-weight infant. J Clin Ultrasound. 1985. 13:506–508.

7. Geirsson RT, Ricketts NE, Taylor DJ, Coghill S. Prenatal appearance of a mesoblastic nephroma associated with polyhydramnios. J Clin Ultrasound. 1985. 13:488–490.

8. Ohmichi M, Tasaka K, Sugita N, Kamata S, Hasegawa T, Tanizawa O. Hydramnios associated with congenital mesoblastic nephroma: a case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1989. 74:469–471.

9. Goldstein I, Shoshani G, Ben-Harus E, Sujov P. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital mesoblastic nephroma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002. 19:209–211.

10. Gordillo R, Vilaro M, Sherman NH, Phillips M, Hoyer JR, Rosenberg HK. Circumscribe- d renal mass in dysplastic kidney. J Ultrasound Med. 1987. 6:613–617.

11. Ambrosino MM, Hernanz-Schulman M, Horii SC, Raghavendra BN, Genieser NB. Prenatal diagnosis of nephroblastomatosis in two siblings. J Ultrasound Med. 1990. 9:49–51.

12. Rempen A, Kirchner T, Frauendienst-Egger G, Hocht B. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma. Fetus. 1992. 2:1–5.

13. Campagnola S, Fasoli L, Flessati P, Sulpasso M, Balter R, Pea M, Caudana R. Congenital cystic mesoblastic nephroma. Urol Int. 1998. 61:254–256.

14. Diana W, Timothy M, Mary E. Fetology: diagnosis and management of the fetal patient. 2000. 849–852.

15. Haddad B, Haziza J, Touboul C, Abdellilah M, Uzan S, Paniel BJ. The congenital mesoblastic nephroma: a case report of prenatal diagnosis. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1996. 11:61–66.

16. Shibahara H, Mitsuo M, Fujimoto K. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of a fetal renal mesoblastic nephroma occuring after transfer of a cryopreserved embryo. Hum Reprod. 1999. 14:1324–1327.

17. Pettinato G, Manivel JC, Wick MR, Dehner LP. Classical and cellular (atypical) congenital mesoblastic nephroma:a clinicopathologic, ultrastructual, immunohisto-chemical, and flow cytometric study. Hum Pathol. 1989. 20:682–690.

18. Ehman RL, Nicholson SF, Machin GA. Prenatal sonographic detection of congenital mesoblastic nephroma in a monozygotic twin pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 1983. 2:555–557.

20. Blank E, Neerhout RC, Burry KA. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma and polyhydramni- os. JAMA. 1978. 240:1504–1505.

21. Bechwith JB, Weeks DA. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma: when should we worry? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986. 110:98–99.

22. Joshi VV, Kasznicka J, Walters TR. Atypical mesoblastic nephroma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986. 110:100–106.

23. Speleman F, van den Berg E, Dhooge C. Cytogenetic and molecular analysis of cellular atypical mesoblastic nephroma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998. 21:265–269.

24. Cin DP, Lipcsei G, Hermand G, Boniver J, van den Berghe H. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma and trisomy 11. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998. 103:68–70.

25. Fuchs IB, Henrich W, Brauer M, Stover B, Guschmann M, Degenhardt P, Dudenhausen JW. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital mesoblastic nephroma in 2 siglings. J Ultrasound Med. 2003. 22:823–827.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download