Abstract

A 68-year-old woman presented with pain in her left eye. Necrosis with calcium plaques was observed on the medial part of the sclera. Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated from the culture of the necrotic area. On systemic work-up including serum and urine electrophoresis studies, the serum monoclonal protein of immunoglobulin G was detected. The patient was diagnosed with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and fungal scleritis. Despite intensive treatment with topical and oral antifungal agents, scleral inflammation and ulceration progressed, and scleral perforation and endophthalmitis developed. Debridement, antifungal irrigation, and tectonic scleral grafting were performed. The patient underwent a combined pars plana vitrectomy with an intravitreal injection of an antifungal agent. However, scleral and intraocular inflammation progressed, and the eye was enucleated. Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated from the cultures of the eviscerated materials. Giemsa staining of the excised sclera showed numerous fungal hyphae.

Fungal scleritis is a rare cause of infectious scleritis that is associated with a poor prognosis because there is minimal penetration of topical and systemic antifungals into the nearly avascular sclera. Moreover, early diagnosis is often challenging because microorganisms can penetrate into the deep intrascleral lamellae and remain there for a long period of time without causing an inflammatory response [1,2].

Monoclonal gammopathy is defined by the presence of monoclonal proteins in the serum and urine. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a diagnosis given to patients with monoclonal gammopathy who have no features of multiple myeloma or other malignant disorders. Although the etiology of monoclonal gammopathy is not exactly known, it has been suggested that this condition is associated with chronic inflammation and infection [3-5]. Moreover, patients with monoclonal gammopathy have decreased productions of normal immunoglobulins and experience overall suppression of the immune system. Therefore, infections in patients with monoclonal gammopathy require prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment in order to reduce morbidity [6].

In this paper, we report a case of Aspergillus fumigatus scleritis in a patient with MGUS. To the best of our knowledge, fungal scleritis has not been previously reported in association with MGUS.

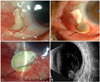

A 68-year-old Asian woman presented with pain and redness in her left eye over the past two months. She had undergone a pterygium excision on the same eye three years prior to presentation. Otherwise, she had no history of ocular trauma or surgery. Her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/200 in the left eye. On slit lamp biomicroscopy, a nummular area of avascular sclera with necrosis and calcium plaque deposition was observed on the nasal portion of the eye. The surrounding vessels were engorged (Fig. 1A). Serological testing that included antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rheumatoid factor , venereal disease research laboratory test, and human leukocyte antigen-B27 revealed no positive results. However, a reversal of the albumin-to-globulin ratio was noted in the serum, and a monoclonal protein of immunoglobulin G was detected on serum protein electrophoresis and on immunofixation electrophoresis. The calcium plaque was removed, and a culture from the necrotic area was performed, which isolated Aspergillus fumigatus. The patient was diagnosed with fungal scleritis and monoclonal gammopathy. Topical and oral antifungal treatments were initiated using 0.3% amphotericin (Fungizone®; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA) and 1% voriconazole (Vfend®; Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) eye drops every hour and oral fluconazole 200 mg (Plunazole®; Dae Woong, Seoul, Korea) daily. However, scleral necrosis progressed and a perforation developed. The necrotic material was debrided, the sclera was vigorously irrigated with amphotericin, and tectonic scleral grafting was applied over the affected area. Intravenous amphotericin, 40 mg daily, was added to the treatment regimen. However, scleral melting extended into the surrounding sclera (Fig. 1B), and scleral perforation was found at the previous scleral graft site. Debridement, irrigation with amphotericin, and tectonic scleral grafting were repeated. Despite intensive topical and intravenous antifungal treatments, scleral necrosis progressed (Fig. 1C) and vitreous inflammation was complicated (Fig. 1D). Under a presumed diagnosis of fungal endophthalmitis, we performed a pars plana vitrectomy with an intravitreal injection of amphotericin (1 mg/0.1 mL, 0.1 mL). During vitrectomy, we noted a large retinal inflammatory infiltrate associated with retinal edema and detachment. Scleral ulceration and intraocular inflammation progressed, and the eye was enucleated. Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated in the cultures of the eviscerated materials. Pathologic examination using Giemsa staining showed numerous fungal hyphae in the excised sclera (Fig. 2).

A diagnosis of fungal scleritis can be confirmed using cultures. However, the diagnosis of fungal scleritis is often delayed because the symptoms and signs of scleritis are difficult to differentiate from those of immune-mediated, necrotizing scleritis [1,2]. Moreover, the chronicity of the disease and the fungus' slow growth and penetration in cultures complicate the early diagnosis of fungal scleritis [1,2]. However, because poor outcomes can result from late diagnoses, clinicians must have a high index of suspicion to make an early diagnosis of fungal scleritis in cases of necrotizing scleritis combined with a subconjunctival abscess or discharge, as well as in patients with a history of ocular trauma or surgery. Moreover, efforts to isolate microorganisms should be made by scleral biopsy, scrapings, and cultures in cases suspicious for fungal infection.

For the treatment of fungal scleritis, surgical treatment can be used in combination with topical and systemic antifungal therapies [7]. Various antifungals have been used to treat fungal scleritis; however, the treatment is often limited by the poor intraocular penetration of traditional antifungals [8]. In this case, we used voriconazole, which has been proven to have in vitro susceptibility to ocular fungal pathogens [9] and can achieve an effective intraocular concentration when administered topically [10]. Surgical debridement and cryotherapy are reported to promote responses to antifungal agents, although we did not perform cryotherapy in our patient. It is possible that cryotherapy in our patient might have prevented the fungal scleritis from progressing.

MGUS is characterized by the presence of abnormal monoclonal proteins in the serum and urine. 'Unknown significance' indicates that patients with MGUS alone have no features of multiple myeloma or other malignant disorders. As with our patient, MGUS patients do not show any clinical manifestations suggestive of multiple myeloma, including pathologic fracture from lytic bone lesions or renal failure from monoclonal proteins. However, some patients may eventually progress to symptomatic monoclonal gammopathy based on laboratory abnormalities and clinical features. A long-term study of MGUS patients found that approximately 1% of patients developed symptomatic monoclonal gammopathy each year [11].

The etiology of monoclonal gammopathy is unknown. However, many studies have demonstrated that repeated or chronic stimulation of the immune system through autoimmune, infectious, or inflammatory disorders may lead to monoclonal gammopathy [3-5]. In our patient, MGUS was detected in combination with an uncontrolled scleral inflammation. After the inflammation was controlled by enucleation, the reversal of the albumin-to-globulin ratio gradually decreased. These findings suggest that sustained scleral inflammation caused by the fungal infection might have induced the monoclonal gammopathy in this patient. Moreover, patients with monoclonal gammopathy have decreased productions of normal immunoglobulins, which causes overall suppression of the immune system [6]. Therefore, the poor prognosis and intractable fungal scleritis in this patient might be attributable to the immune-compromised state associated with the monoclonal gammopathy.

In summary, we report a case of refractory fungal scleritis complicated by MGUS. Although rare, the possibility of the development of immunologic abnormalities should be considered in cases of infectious scleritis that progress despite intensive anti-infective chemotherapy.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Anterior segment photography and ultrasonography of the left eye. (A) At presentation, scleral necrosis and calcium plaque deposition were observed, with engorged vessels in the surrounding area. (B,C) Despite intensive medical and surgical treatments, scleral melting lead to perforation and progressed inferiorly into the previous scleral graft site (arrows). (D) Scleritis progressed to endophthalmitis. Vitreal inflammation was found on the ultrasonography.

References

1. Huang FC, Huang SP, Tseng SH. Management of infectious scleritis after pterygium excision. Cornea. 2000. 19:34–39.

2. Fincher T, Fulcher SF. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenge of aspergillus flavus scleritis. Cornea. 2007. 26:618–620.

3. Brown LM, Gridley G, Check D, Landgren O. Risk of multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among white and black male United States veterans with prior autoimmune, infectious, inflammatory, and allergic disorders. Blood. 2008. 111:3388–3394.

4. Garcia Marrero RD, Alonso Socas MM, Oramas Rodriguez J, et al. Several episodes of bacterial infections in a patient with monoclonal gammapathy of undetermined significance. An Med Interna. 2006. 23:452.

5. Mseddi-Hdiji S, Haddouk S, Ben Ayed M, et al. Monoclonal gammapathies in Tunisia: epidemiological, immunochemical and etiological analysis of 288 cases. Pathol Biol. 2005. 53:19–25.

6. Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, AL amyloidosis, and related plasma call discorders: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006. 81:693–703.

7. Rodriguez-Ares MT, De Rojas Silva MV, Pereiro M, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus scleritis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1995. 73:467–469.

8. Stewart RM, Quah SA, Neal TJ, Kaye SB. The use of voriconazole in the treatment of Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007. 91:1094–1096.

9. Marangon FB, Miller D, Giaconi JA, Alfonso EC. In vitro investigation of voriconazole susceptibility for keratitis and endophthalmitis fungal pathogens. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004. 137:820–825.

10. Thiel MA, Zinkernagel AS, Burhenne J, et al. Voriconazole concentration in human aqueous humor and plasma during topical or combined topical and systemic administration for fungal keratitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007. 51:239–244.

11. Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346:564–569.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download