Abstract

To report a case of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis after intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA). A 77-year-old woman with macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) developed peripheral retinitis 4 months after IVTA. A diagnostic anterior chamber paracentesis was performed to obtain DNA for a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for viral retinitis. The PCR test was positive for CMV DNA. Other tests for infective uveitis and immune competence were negative. Four months after presentation, gancyclovir was intravitreously injected a total of 5 times, and the retinitis resolved completely. CMV retinitis is a rare complication of local immunosuppression with IVTA. It can be managed with timely injection of intravitreal gancyclovir until recovery from local immunosuppression.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis remains the most common opportunistic ocular infection in immunocompromised patients.1 Patients with immunosuppression caused by various disease states including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and those with iatrogenic immunosuppression from chemotherapy and immune modulators are at risk.1 We present a case of CMV retinitis after intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA) in an immunocompetent woman with no other immunocompromising diseases.

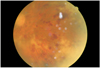

A 77-year-old woman with a history of hypertension was referred to our clinic in September 2006 for a 2-week history of blurred vision in her right eye. She had received an intravitreal injection of 4 mg of triamcinolone acetonide in her right eye for macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) 4 months previously. Her right eye visual acuity was significant for light perception only, and ophthalmic examination of the right eye showed many cells in the anterior chamber and vitreous, multiple retinal hemorrhages and peripheral circumferential retinitis (Fig. 1). Serologic tests for infectious uveitis caused by herpes zoster virus (HZV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), CMV, toxoplasmosis, and syphilis (VDRL), and a test for human immunodeficiency virus, were performed. The patient tested seronegative for HZV, HSV, CMV, toxoplasma, and HIV, and VDRL was non-reactive. Before starting an oral corticosteroid, intravenous injection of acyclovir (2000 mg/day 4 times a day) was started. Because of a presumed diagnosis of acute retinal necrosis or CMV retinitis, diagnostic anterior chamber paracentesis was performed, and an aqueous humor sample was sent for analysis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for HZV, HSV, CMV and toxoplasmosis. An intravitreous gancyclovir injection (1.7 mg) was performed immediately after aqueous sampling. The aqueous humor PCR sample tested positive only for CMV.

Five days after the gancyclovir injection, the number of inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber decreased to trace amounts only, and the vitreous was cleared. Argon laser photocoagulation between the area of retinitis and the normal retina was performed on the patient's right eye. Three weeks after the first gancyclovir injection, the patient presented with an aggravated retinal lesion and chamber reactions in the right eye. A second intravitreal gancyclovir (1.7 mg) injection was performed. An additional two intravitreal gancyclovir (1.7 mg) injections were performed at 2 weeks and 6 weeks after the second injection.

Two weeks after the final gancyclovir injection, examination of the right eye revealed much improved peripheral retinal necrosis with persistent retinitis at the inferior periphery. Nine weeks after the last injection (4 months after the patient's first visit to our clinic), the retinitis was completely resolved. Clear anterior chamber and mild sustained vitreous opacity were noted. The patient's final resultant vision in her right eye was significant for hand motion. Her right eye has remained free of retinitis since.

CMV is a ubiquitous human virus and 50-80% of adults in the United States harbor anti-CMV antibodies.22,3 Seroprevalence among lower socioeconomic groups, residents of developing countries, and homosexual men can exceed 90%.4 Acquisition of the virus occurs through placental transfer, breast feeding, saliva, sexual contact, blood transfusions, and organ or bone marrow transplants. Infection with CMV leads to life-long persistence; however, in healthy individuals, the virus becomes dormant and remains latent.1 Reactivation occurs in patients with immature or compromised immune systems.1 In iatrogenically immunosuppressed patients after organ or bone marrow transplantation, CMV retinitis is a rare complication.5,6 Recently, 4 cases of CMV retinitis after intravitreal steroid application in immunocompetent patients have been reported.7-9 In comparison with these previously published cases, our patient had no medical problems such as diabetes mellitus or Behcet's disease that could have impaired her immunity.7-9 Local immunosuppression may be strong enough to allow CMV to replicate and lead to retinitis. In our case, symptomatic retinitis developed 4 months after the injection of intravitreal triamcinolone. The retinitis was completely resolved 8 months after IVTA. The local immunosuppressive effect of IVTA is thought to persist up to 8 months after injection. The poor visual outcome in this case was thought to be mainly due to the patient's baseline disease. Timely treatment with intravitreal injection of gancyclovir until local immune recovery may be effective for local immunosuppressioninduced CMV retinitis.

Ophthalmologists using intravitreal triamcinolone injections should be aware of the potential risk of subsequent CMV retinitis. Early diagnosis and treatment with intravitreal injections of gancyclovir until recovery is obtained may prevent further complications.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Wiegand TW, Young LH. Cytomegalovirus retinitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2006. 46:91–110.

2. Marshall GS, Rabalais GP, Stewart JA, et al. Cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in women bearing children in Jefferson County, Kentuchy. Am J Med Sci. 1993. 305:292–296.

3. Pass RF. Epidemiology and transmission of cytomegalovirus. J Infect Dis. 1985. 152:243–248.

4. Sohn YM, Oh MK, Balcarek KB, et al. Cyomegalovirus infection in sexually active adolescents. J Infect Dis. 1991. 163:460–463.

5. Crippa F, Corey L, Chuang EL, et al. Virological, clinical, and ophthalmologic features of cytomegalovirus retinitis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2001. 32:214–219.

6. Gallant JE, Moore RD, Richman DD, et al. Incidence and natural history of cytomegalovirus disease in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease treated with zidovudine. The Zidovudine Epidemiology Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1992. 166:1223–1227.

7. Saidel MA, Berreen J, Margolis TP. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after intravitreous triamcinolone in an immunocompetent patient. Am J of Ophthalmol. 2005. 140:1141–1143.

8. Ufret-Vincenty RL, Singh RP, Lowder CY, Kaiser PK. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after fluocinolone acetonide (Retisert™) implant. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007. 143:334–335.

9. Delfer MN, Rougier MB, Hubschman JP, et al. Cytomegalovirus retinitis following intravitreal injection of triamcinolone: report of two cases. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007. 85:681–683.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download