Abstract

This study analyzed a hospital-based study to investigate the incidence and clinical features of ocular traumatic emergencies in Korea. Over a 6-year period, 1809 patients with ocular traumatic emergency each individually underwent clinical study including subject characteristics, type of ocular emergency, disease severity, etiology of ocular trauma, injury location, cause of decreased visual acuity, management of ocular injury, and final visual acuity. The homogeneity of each finding of the clinical features of ocular traumatic emergency was tested by an X2 test at a 95% level of certainty. During follow-up periods ranging from 3 days to 23 months (mean 2.0 months), the 1809 patients with ocular traumatic emergency, 1183 males (65.4%) and 626 females (34.6%), were studied. The incidence of ocular emergencies peaked in the third decade of life, irrespective of gender (P < 0.05). Corneal abrasion was the most common etiology among 1,552 (85.8%) closed injuries, and corneal laceration among 257 (14.2%) open injuries (P < 0.05). There were 542 cases (30%) of severe ocular injury, such as penetrating ocular injury, blow out fracture, and intraocular foreign body (IOF), and 1267 (70%) of less severe ocular injury, such as superficial ocular injury or contusion. The most common etiology of severe ocular injury was penetrating ocular injury, and that of less severe injury was corneal injury (P < 0.05). The main causative activity of ocular injuries was work in 631 cases (34.9%), assault in 398 (22.0%), play in 278 (15.4%), traffic accidents in 145 (8.0%) and sports in 128 (7.1%). Five hundred and fifty-four cases (32.5%) underwent surgical intervention. There was an improvement of visual acuity in 502 cases (70.1%), no change in 122 (17.0%), and worsening in 92 (12.9%). We suggest that preventive educational measures be instigated at workplaces to reduce the incidence of ocular traumatic emergency, especially severe ocular injury.

Diagnoses of ocular traumatic emergencies are grouped as traumas, which are divided into open and closed injury.1 Careful examination and appropriate treatment are important factors because ocular traumatic emergencies may have a poor visual prognosis even when seemingly mild. In addition, ocular trauma is only one of several important causes of preventable visual morbidity and blindness.2-5

Since any study based on ocular traumatic emergency is limited by the accuracy of the code used, the industrial and regional differences, and the limited number of subjects, there is little reliable information on the incidence, severity, and etiologies of ocular emergencies in Korea. Especially, data on the epidemiological information concerned with ocular emergencies on eye trauma is rare.

Therefore, we retrospectively investigated the incidence, severity, and clinical features of ocular trauma in one emergency department, and compared the epidemiology of ocular injury requiring emergency management with that in western countries by using various factors.

The authors reviewed the medical records of 1,809 patients who presented with ocular complaints to the Emergency Department of the Pusan National University Hospital (PNUH) between January 1994 and December 2000. PNUH is the largest tertiary hospital in Pusan, and sees a wide variety of cases concerned with ocular emergency. PNUH is a 1200-bed, regional ophthalmic center serving a population of approximately 3.8 million and has an annual Emergency Department attendance of 40,000 patients. Being a tertiary referral center, most ocular emergencies are referred to this hospital and it is set in the heart of Pusan, the second largest city in Korea. Patients seen in the Emergency Department of PNUH are first managed at the ophthalmic unit, which is manned 24 hours a day by Ophthalmology residents and professors. For all cases, the resident will normally take a history, perform an ocular examination and dispense medication or other treatments, with the help of nursing staff. We retrospectively analyzed the patient characteristics, types of ocular emergency, disease severities, causes of ocular trauma, injury locations, causes of decreased visual acuity, management of ocular injury, and final visual acuity. In addition, we classified the patients into two groups by the severity of ocular traumatic injury: severe ocular injury was penetrating eye injury, hyphema, blow-out fracture, and intraocular foreign body (IOF); and less severe ocular injury was superficial ocular injury or contusion.5

A questionnaire was used to request demographic data, details about the injury (date, time, place, mechanism), and history of prior eye injuries. All patients sustaining acute eye injuries, including orbital fractures, periorbital soft-tissue injuries, optic nerve injuries, and injuries to the globe, formed the subset of cases for this analysis. For injuries occurring at work, respondents were asked to state the type of work in which they were involved. For injuries associated with sports, information on the type of sport and the level of expertise was requested. Diagnoses and the disposition of patients were added by the doctor to the form completed by the patients.

Written permission to contact the patient for follow-up information was requested on each questionnaire. Patients who were seen for late complications of eye injury were considered cases only if the original injury occurred during the study period. Patients who complained of eye pain or injury, but for whom there were no objective findings, were excluded. The final visual acuity was defined as the best corrected visual acuity on the final visit to the emergency center.

The homogeneity of each finding of the ocular features of emergency was tested by an x2 test. A P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 1,809 patients with ocular traumatic emergencies, 1,183 males (65.4%) and 626 females (34.6%), were studied. The mean age of the subjects was 29.5 years (range: 2 months to 89 years), and was older in males (mean 32.3 years) than in females (mean 29.9 years). There were 831 cases (45.9%) of right eye involvement, 905 cases (50.1%) of left, and 73 cases (4.0%) of both. The mean follow-up period was 2.0 months, ranging from 3 days to 23 months.

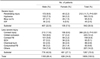

Ocular traumatic injuries were divided into 1,552 closed (85.8%) and 257 open (14.2%) injuries. Corneal abrasion was the most common etiology with 366 cases (20.2%) among the 1,552 closed injuries, followed by ocular contusion, hyphema, and corneal foreign body. Corneal laceration was the most common etiology with 123 cases (6.8%) among the 257 open injuries, followed by scleral laceration, and IOF (Table 1).

The incidence of traumatic ocular injury increased proportionally with increasing age, but a decrease was also noted over the third decade of life. The distribution of traumatic ocular injury was most frequent in the middle age groups, between 10 and 39 years. The prevalence of traumatic ocular injury was higher in males than in females of all ages (Fig. 1).

There were 542 cases of severe injury such as penetrating ocular injury, blow out fracture, hyphema, IOF, and the incidence was higher in males than in females. Less severe injuries, such as superficial ocular injury or contusion, included corneal injury in 366 cases (20.2%), orbital contusion in 220 (12.2%), and corneal foreign body in 159 (8.8%). The prevalence of less severe ocular injury was predominantly higher in males than in females (Table 2). Severe and less severe injury had a peak incidence in the third decade of life and a tendency to decrease after this decade (Fig. 2).

The main sources of eye trauma were work in 631 cases (34.9%), assault in 398 (22.0%), play in 278 (15.4%), traffic accidents in 145 (8.0%) and sports in 128 (7.1%). According to gender, the largest cause in the males was work-related events in 490 cases, (27.1%), whereas in the females it was assault in 166 cases, (9.2%). The most common causative material at the workplace was flying foreign body in 340 cases (18.8%), especially metal and chemical liquid (P < 0.05). In assault, the fist was the most common in 221 cases (12.2%), followed by an instrument in 79 (4.4%) and the foot in 60 (3.3%). In play cases, the hand was the most common in 118 cases (6.5%), followed by slippage, instrument and fall (P<0.05). The incidence of ocular traumatic emergency by causes was predominantly higher in males than in females for most causes except, in play (slippage) and sports (tennis and badminton) (Table 3).

Of all injuries, 34.9% occurred at the workplace, 32.2% at home, and 25% at street or school. The most common location in the males was the workplace and in the females at home (Table 4). Penetrating ocular injury and IOF occupied the highest portion with 78 cases (84.8%) in traumatic cases (P < 0.05) (Table 5). Among 716 cases (25.1%) for which follow-up data was available, 170 cases (23.7%) had a initial visual acuity of less than 20/63, but finally 23 cases (3.3%) had the same visual range (Table 6). There was improvement in 502 cases (70.1%), no change in 122 (17.0%), and worsening in 92 (12.9%) (Fig 3).

Five hundred and fifty-four cases (30.2%) concerned with ocular traumatic emergency were managed by surgical interventions, 204 by corneoscleral suture (33.2%), and 159 by removal of corneal foreign body (25.9%), followed by vitrectomy, anterior chamber washout and conjunctival suture (P < 0.05). The ocular traumatic emergencies were performed by additional combined or repeated surgical procedures; single operation in 501 cases (90.4%), double in 35 (6.3%), and triple in 18 (3.3%) (Table 7).

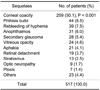

Complications occurred in 517 cases; the most common being corneal opacity in 259 cases (50.1%), followed by phthisis bulbi, rebleeding of hyphema, anophthalmos, secondary glaucoma and vitreous opacity (P < 0.05) (Table 8).

Ocular trauma is an important cause of preventable visual morbidity, particularly among the younger age groups, and is more prevalent before 40 years of age in males due to their frequent social activity.2-5 Forty-four percent of ocular emergencies occurred by trauma with an approximate 1.9 to 1 male to female ratio, and the peak age was in the third decade of life in China.6 In the United States and elsewhere, some studies have been published showing that ocular trauma developed predominantly in males (72-90%) and the young, with a majority under 30 years of age.4,6-9 This study showed a male to female ratio of about 1.9 to 1, and the overall prevalence was 65.4% in males with a majority in the third decade of life. It seems that the incidence and prevalence of ocular trauma between oriental and western countries are similar.

Ocular trauma is divided into open and closed injury. In the United States, the prevalence of closed ocular injury was more predominant than open ocular injury, and was higher in males than in females.6 We studied 2,856 patients with ocular emergency in Korean population. There were 1,809 cases (63.3%) of trauma and 1,047 cases (36.6%) of non-trauma. The incidence was higher in males (65.4%) than in females (34.6%) (data not shown). The prevalence of closed ocular injury was about six times higher than that of open ocular injury in our study. There was no difference in the prevalence by type of ocular trauma between western countries and Korea.

We classified penetrating eye injury, hyphema, blow-out fracture, and IOF as severe injuries5 and found the distribution of severe ocular injury to be more frequent in the middle age groups, between 10 and 39 years. The high-risk group is generally known to be between the ages of 15 and 64 years in males in the United States3,4 and our results are in agreement. Corneal abrasion and foreign body were the most common etiologies of ocular trauma, followed by conjunctival foreign body, subconjunctival hemorrhage, and ocular contusion.5 In our study, corneal abrasion was the most common ocular trauma, followed by ocular contusion, traumatic hyphema and corneal foreign body. Thus may be due to the social activities of peoples regardless of race or region.

The incidence of industrial ocular injuries was higher in males, and in the third decade of life, followed by the fourth and fifth decades.11 Among the causative materials, iron pieces were the most common, followed by wire and nails, chemical agents, hot water and wood.11 In our results, most work-related ocular trauma occurred in males, and in the fourth of life, followed by the third and fifth decades. Assault and play were more prevalent before 20 years of age, which may be due to the accidental traumas of childhood or the social problems of adolescence.

In western countries, the most common causes of injury were assaults, followed by work-related events, sports and recreational activities, motor vehicle crashes, and falls.5 There were 258 penetrating eye injuries of which 69 cases (37.1%) were due to work-related accidents, and predominantly occurred in males under 40 years.12 Work-related events were the most common circumstance, and the number of male patients in the middle age groups, between 10 and 39 years, was more than 2.5 times that of the females in our study. This incidence with causes of ocular injury between western countries and Korea was due to cultural conditions and the socioeconomic environment like the industrial state of each country.

The most common location of ocular trauma was the home (34.7%), followed by work-place (17.9%), and street (9.8%) in the United States.14 According to location in our study, more than half of the traumas occurred at the workplace (34.9%) and the home (32.2%), and the most frequent location in the male group was the workplace and in the female, the home. This difference may be explained by differences in the main places, where they work, and will be gradually reduced as the social activities of females increase.11

In western countries, one report showed that work related injuries account for 22% of all penetrating eye injuries.15 This low incidence of ocular trauma in western countries compared to that of our study in Korea was associated with the greater use of protective devices and education in the industrial environment. Although ocular safety equipment often inconvenient, it is essential to protect against the risk and consequences of an eye injury. However, there were no significant gender differences in traumas at school and street because traumas at school age and traffic accidents occur regardless of gender.

The reported surgical procedures of ocular injuries in the emergency department included primary closure of eyelid and face and corneal suture,10 while other studies have reported that corneoscleral suture, primary lid suture and canalicular reconstruction were common surgical interventions for ocular injuries.11,13 In our study, the common surgical interventions were corneoscleral suture and removal of corneal foreign bodies. Among 554 patients managed by surgical interventions, 501 (90.4%) were managed by a single emergency operation after admission whereas 53 (9.6%) underwent additional combined or repeated surgical procedures.

A few studies in other countries have reported that about 3-15% of patients required hospitalization14,15 and that the duration was less than 1 week for 36.8% of patients.10 According to our results, 554 cases (30.2%) were hospitalized for operation, the average duration of hospitalization was 11 days, and the duration of most cases was less than 20 days (data not shown). This difference in the incidence and duration of hospitalization between western countries and Korea may be explained by the number of subjects including trauma or non-trauma, hospital quality with or without primary care unit, and socioeconomic state.

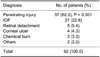

Visual acuity was improved after treatment in most cases but decreased in complicated cases. There was improvement in 502 cases (70.1%), no change in 122 (17.0%), and worsening in 92 (12.9%). Decreased visual acuity was defined as a decrease of two lines on the ETDRS chart from the first visual acuity measurement at the emergency department of PNUH. In western countries, twenty-six (13.2%) had a poor visual outcome at final discharge from follow up in UK.17 The outcome of poor visual acuity did not demonstrate any important differences by ocular management in ocular traumatic emergency between western countries and Korea. The most common causes of decrease in vision were penetrating eye injuries in 57 cases (62%) and IOF in 21 (22.8%), followed by retinal detachment and corneal ulcer. It seems to be that the final visual acuity depends on the severity of traumatic ocular injury, especially penetrating eye injury. To escape from penetrating eye injury, protection from the risk and consequences of an eye injury is essential.

The most common complication of ocular emergencies after treatment in our study was corneal opacity (50.1%), and the other incidences were between 34.1% and 41.2% in Korea,10,13 compared to under 20% in western countries.14,15 This difference of incidence between Korea and western countries may be explained by the deficiency in Korea of ocular protective devices and education associated with industrial tasks. Furthermore, as more than two-thirds of work-related ocular emergencies in Pusan occurred by flying foreign bodies and UV radiation, adequate eye protection like safety glasses and industrial safety-education at the workplace will go a long way to reducing the incidence of ocular traumatic emergency, especially severe ocular injury.

Figures and Tables

Notes

References

1. Kuhn F, Morris R. A standardized classification of ocular trauma. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1996. 614:399–403.

2. Canavan YM, O'Flaherty MJ, Archer DB, Elwood JH. A 10 year survey of injuries in northern Ireland 1967-76. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980. 64:618–625.

3. Klopfer J, Tielsch JM. Ocular trauma in the United States Eye injuries resulting in hospitalization, 1984 through 1987. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992. 110:838–842.

4. Tielsch JM, Parver L, Shankar B. Time trends in the incidence of hospitalized ocular trauma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989. 107:519–523.

5. Karlson TA, Klein BEK. The incidence of acute hospital-treated eye injuries. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986. 104:1473–1476.

6. Tsai CC, Kau HC, Kao SC, Liu JH. A review of ocular emergencies in a Taiwanese medical center. Chung Hua I Hsueh Tsa Chih. 1998. 61:414–420.

7. Morris RE, Witherspoon CD, Helms HA Jr, Feist RM, Byrne JB Jr. Eye injury registry of Alabama (preliminary report): Demographics and prognosis of severe eye injury. South Med J. 1987. 80:810–816.

8. Thoradson U, Ragnarsson AT, Gudbrandsson B. Ocular trauma: Observation in 105 patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 1978. 57:922–928.

9. Maltzman BA, Pruzon H, Mund ML. A survey of ocular trauma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1976. 2:285–290.

10. Lee KJ, Oh JH. A statistical observation of the ocular injuries. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1990. 31:229–239.

11. Kim SS, Yoo JM. A clinical study of industrial ocular injuries. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1988. 29:393–403.

12. Patel BC, Morgan H. Work-related penetrating eye injuries. Acta Ophthalmol. 1991. 69:377–381.

13. Chang Y, Oh S, Chi NC. A clinical observation of ocular injuries of inpatients. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1993. 34:257–263.

14. Nash EA, Margo CE. Patterns of emergency department visits for disorders of the eye and ocular adnexa. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998. 116:1222–1226.

15. Dannenberg AL, Parver LM, Brechner RJ, Khoo L. Penetrating injuries in the workplace. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992. 110:843–849.

16. Voon LW, See J, Wong TY. The epidemiology of ocular trauma in Singapore: perspective from the emergency service of a large tertiary hospital. Eye. 2001. 15:75–81.

17. Desai P, MacEwen CJ, Baines P, Minassian DC. Incidence of cases of ocular trauma admitted to hospital and incidence of blinding outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996. 80:592–596.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download